Revenue recognition under Accounting Standards Codification Topic 606 (“ASC 606”) significantly changed accounting requirements by standardizing how revenue is identified, measured, and reported. While this standard has been in place for several years, its practical application for companies will constantly evolve as business changes. Let’s review the five-step model of ASC 606. Each step requires careful analysis and judgment, particularly when handling complex contracts or bundled goods and services.

ASC 606-10-20 defines revenue as, “Inflows or other enhancements of assets of an entity or settlements of its liabilities (or a combination of both) from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or other activities that constitute the entity’s ongoing major or central operations.” It is important to note that this standard excludes other types of income, such as gains.

In this article, we revisit the five-step model and share key insights from our experience as a certified public accounting firm helping clients navigate these requirements as part of our experience in auditing private and public companies.

The Five-Step Model for Revenue Recognition

The main principle of this revenue model requires a reporting entity to recognize revenue to depict the transfer of goods or services to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration that it expects to be entitled to in exchange for those goods or services. The standard lays out the following five-step model for revenue recognition:

Step 1: Identify the Contract

The foundation of revenue recognition lies in identifying whether a valid contract exists with a customer involving provision of goods or services that are an output of the entity’s ordinary activities in exchange for consideration. A contract must meet specific criteria:

- Both parties have approved the contract

- The rights and payment terms can be identified

- There is commercial substance, meaning the risk, timing, or amount of the reporting entity’s future cash flows will change as a result of the contract

- It is probable that the entity will collect substantially all of the consideration

Let’s look at some challenges and examples:

Key Challenges: Companies sometimes overlook the need to evaluate whether multiple contracts should be combined. When contracts are entered into near the same time with the same customer, they may need to be treated as a single arrangement if they share a commercial objective. In addition, ambiguity in contract terms can complicate recognition, such as unsigned agreements or vague performance obligations. Additionally, companies must consider customary business practices or industry standards, which may not always be explicit in contracts.

Example: A software company agrees to deliver a custom platform but does not finalize payment terms until development is underway. Without clearly defined rights and payment terms or established business practices, this agreement may not initially qualify as a contract under ASC 606.

Step 2: Identify Performance Obligations

Under the model, a performance obligation is defined as an explicit or implicit promise to provide either (i) a distinct good or service, or (ii) a series of distinct goods or services as defined by the revenue standard. This step often proves challenging because it requires careful analysis to determine whether goods or services are distinct.

Each distinct performance obligation must be:

- Capable of being distinct (the customer can benefit from it alone or with other readily available resources)

- Separately identifiable within the context of the contract

Determining whether a contract has one or multiple performance obligations requires understanding of the interdependence of deliverables.

Example: A construction company agrees to build a house, supplying both materials and labor. Is this a single obligation (construction of a finished house) or multiple obligations (e.g., supply of concrete, lumber, and electrical systems)? If the deliverables are highly interdependent, they are treated as a single performance obligation. However, if sold separately, they might need distinct allocation.

Step 3: Determine the Transaction Price

This step establishes the total consideration expected to be received in exchange for fulfilling the performance obligations. The transaction price calculation must consider:

- Variable consideration (discounts, rebates, refunds)

- Significant financing components

- Non-cash consideration

- Consideration payable to customers

Step 4: Allocate the Transaction Price

Once the total transaction price is determined, it must be allocated to each performance obligation. This allocation is based on the standalone selling price (SSP) of each deliverable, adjusted for discounts or variable pricing.

Important Note: This step only applies when there are multiple performance obligations. However, when it does apply, it’s crucial to:

- Document your SSP methodology

- Consider whether discounts should be allocated proportionally or to specific items being sold based off of historical/observable evidence

- Maintain consistency in your allocation approach

A common challenge here is determining SSP for bundled services, which can require historical data and significant judgment. For example, say a telecommunications provider sells a bundle including internet, cable, and phone services at a discounted price. Allocating the price to each service based on SSP demands market comparisons and precise calculations to ensure compliance with ASC 606.

Step 5: Recognize Revenue

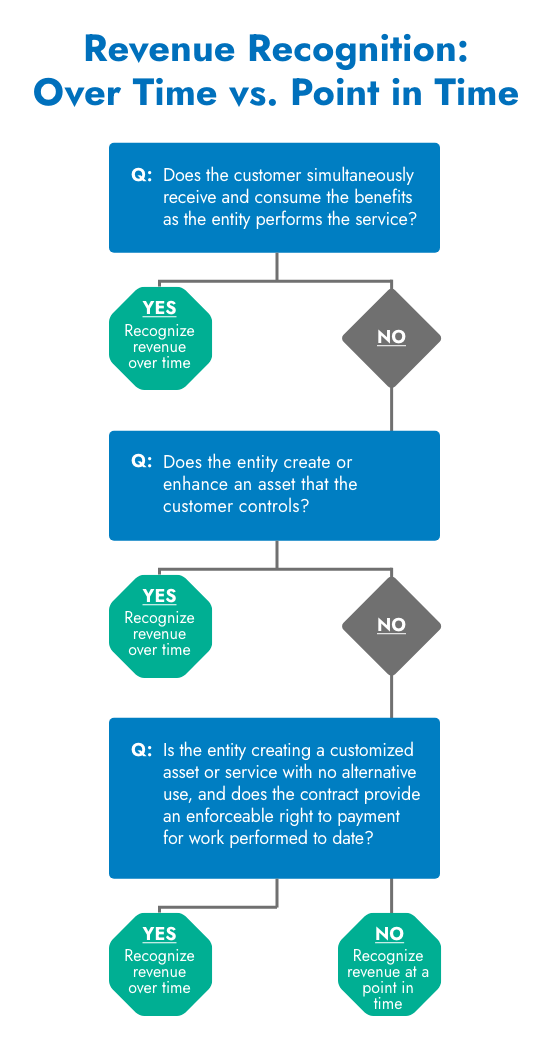

Revenue is recognized when (or as) the performance obligation is satisfied. This could occur over time (e.g., as services are rendered) or at a point in time (e.g., upon delivery of goods). Accountants must use a decision tree to determine whether to recognize revenue over time or upon completion.

Common Application Challenges

As a certified public accounting firm, here are some common challenges to applying the Revenue Recognition Standard.

1. Principal Versus Agent

When more than one party is involved in providing goods or services to a customer, a reporting entity must consider whether it has promised to provide goods or services to customers itself (as a principal) or to arrange for those goods or services to be provided by another party (as an agent). An entity is a principal and therefore records revenue on a gross basis if it controls a promised good or service before transferring that good or service to the customer. An entity is an agent and records as revenue the net amount it retains for its agency services if its role is to arrange for another entity to provide the goods or services.

Example

For example, a contract manufacturer (Company A) enters into an agreement with a distributor (Company B) to provide customized electronic components to an end customer. Depending on specific facts and circumstances, Company A may either be the principal or agent in this scenario:

If Company A receives the order from Company B and produces and delivers the components directly to the end customer, is responsible for fulfilling the contract and bears inventory risk, and sets the gross price charged to Company B, they are likely the principal in this scenario.

However, if Company A instead acts as a fulfillment partner for a large OEM (Company C) in which it earns a commission fee upon product delivery and does not take title to the components, Company C sets pricing and product specifications, and Company A only provides certain assembly services however raw materials and other direct costs are directly sourced from Company C, Company A is likely an agent in this scenario and would record the net revenues from its commission fee.

Principal versus agent consideration is one of the more common application issues we see amongst our clients and requires significant analysis as it has significant implications throughout the five-step model.

2. Contract Modifications

Contract modifications represent one of the most complex areas of revenue recognition under ASC 606. These modifications can occur when parties agree to change the scope or price of a contract, and their accounting treatment can significantly impact revenue recognition timing and amounts. The standard provides three potential approaches for handling modifications, each requiring careful analysis:

- Separate contracts: A separate contract is created when new goods or services are added at their standalone selling price. For example, this might apply if a manufacturing company adds new product lines to an existing supply agreement at standard rates.

- Termination of existing and creation of new contract: Applies when the remaining goods or services are distinct from those already transferred. This often occurs in service industries where the scope of work changes significantly.

- Modification of existing contract: Occurs when the remaining goods or services are not priced at standalone selling price and are not distinct. In these cases, companies must apply a cumulative catch-up adjustment, requiring careful calculations and documentation.

3. Bill-and-Hold Arrangements

Bill-and-hold arrangements present unique challenges in revenue recognition, particularly in manufacturing and distribution industries. These arrangements occur when a company bills a customer for products but retains physical possession of them. While seemingly straightforward, these situations require careful evaluation to determine appropriate revenue recognition timing.

For revenue recognition to be appropriate in a bill-and-hold scenario, companies must satisfy several specific criteria:

Bill-and-Hold Revenue Recognition – Key Criteria

For a company to recognize revenue in a bill-and-hold arrangement, these conditions must all be met:

- Valid Reason:

The business must have a good business reason for the arrangement, for example if the customer specifically requests the business to hold it due to limited space at their own warehouse. - Clearly Marked:

The products must be clearly set aside for that customer and kept separate from other inventory. - Ready to Go:

The products must be finished and ready for delivery, with no work left to do. - Product is Reserved:

The company can’t use the products or sell them to anyone else while holding them for the customer.

Companies must also evaluate whether they are providing custodial services that might constitute a separate performance obligation requiring additional accounting consideration.

4. Warranty Considerations

The treatment of warranties under ASC 606 requires careful analysis to distinguish between assurance-type and service-type warranties, as their accounting implications differ significantly:

- Assurance-type warranties guarantee that a product will function as intended according to agreed-upon specifications. They are accounted for as cost accruals under ASC 460. These represent the basic warranties that customers typically expect when purchasing a product.

- Service-type warranties provide additional services beyond ensuring the product meets basic functionality requirements. These are treated as separate performance obligations under ASC 606, requiring allocation of a portion of the transaction price and potentially affecting the timing of revenue recognition.

For example, if a technology company offers an extended warranty that includes preventative maintenance and software updates beyond fixing basic defects, this would likely constitute a service-type warranty.

Companies often struggle with warranties that contain elements of both types. In these cases, they must exercise significant judgment to determine whether certain warranty provisions extend beyond assuring basic functionality. This evaluation should consider factors like:

- Warranty length

- The nature of promised services

- Whether customers have the option to purchase the warranty separately

It’s important to maintain clear documentation supporting a company’s warranty classification decisions and ensure consistent application of policies across similar arrangements.

Moving Forward

While ASC 606 implementation challenges persist, companies can successfully navigate these requirements by:

- Investing in proper training and documentation

- Establishing clear processes for handling complex scenarios

- Regularly reviewing and updating procedures

- Seeking professional guidance from a certified public accounting firm like Haskell & White when needed

For companies transitioning to GAAP or experiencing growth, understanding these revenue recognition principles is especially important for accurate and consistent financial reporting.

See the FASB’s full ASC 606 accounting standards here.

If your business needs support implementing ASC 606 or improving its revenue recognition processes, Haskell & White’s experienced team is here to help your team with the accounting standard. Contact us today to learn more.